For hundreds of years, the petition has given British citizens a voice in Parliament. No matter your job, class, religion, age or gender, anyone who can sign their name can let the government know what’s bothering them.

Whilst petitions used to be physical documents, we can now petition the government online through the official parliamentary petitions website. If any petition gains 10,000 signatures, the government promises to respond. “What a blessing!” I hear you cry; “Why, we shall surely be in Utopia this time next Tuesday!”

Well…

The government’s online petition website is both a blessing and a curse. On the plus side we can easily let the government know whatever is bothering us. On the downside, we can easily let the government know whatever is bothering us:

The government’s online petition website is both a blessing and a curse. On the plus side we can easily let the government know whatever is bothering us. On the downside, we can easily let the government know whatever is bothering us:

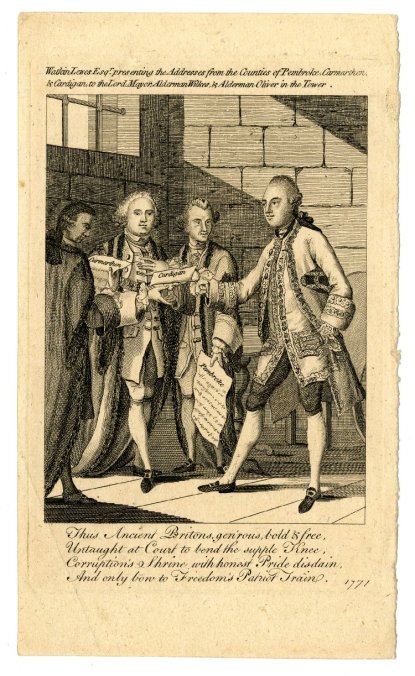

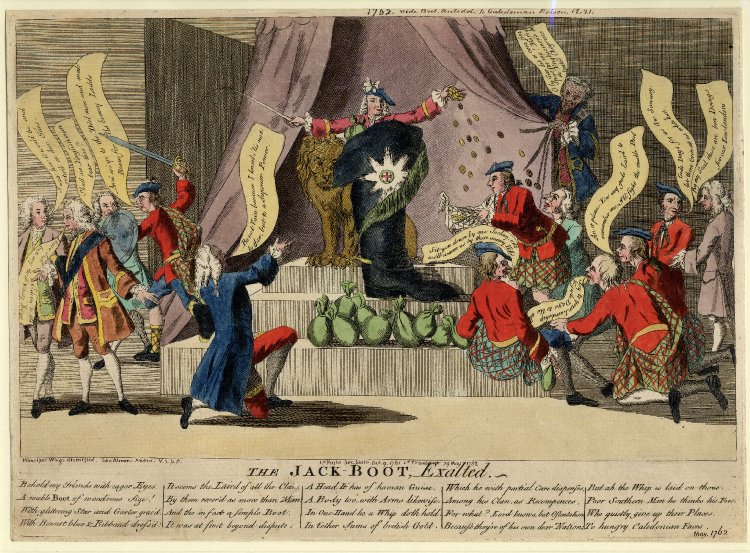

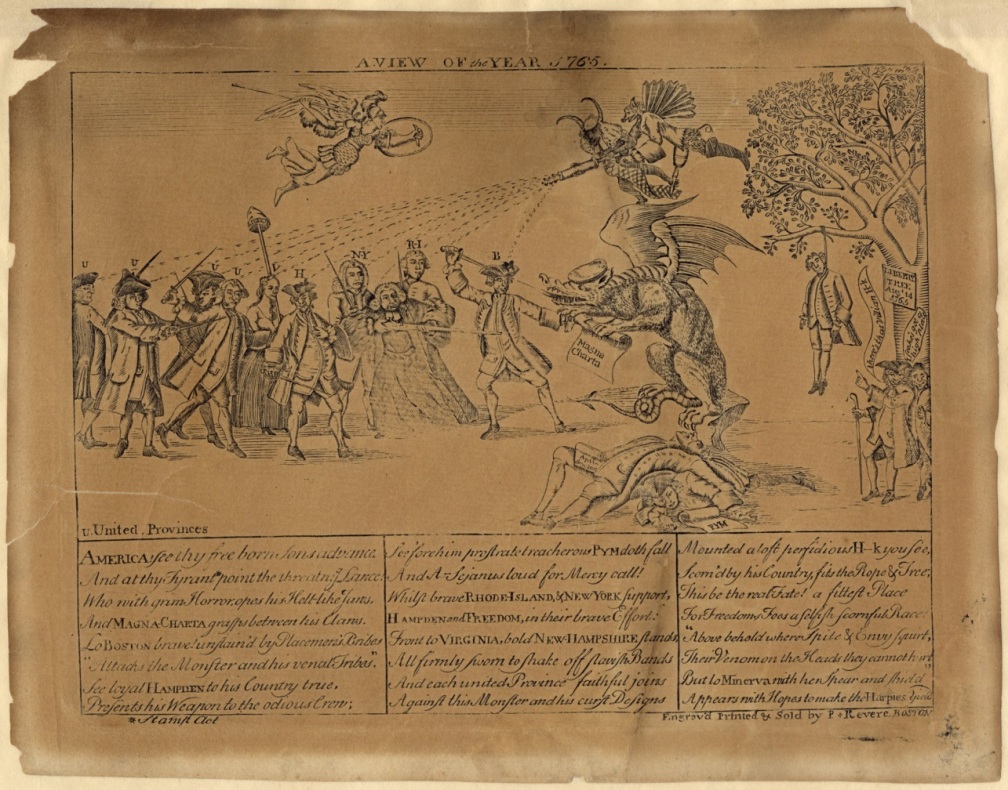

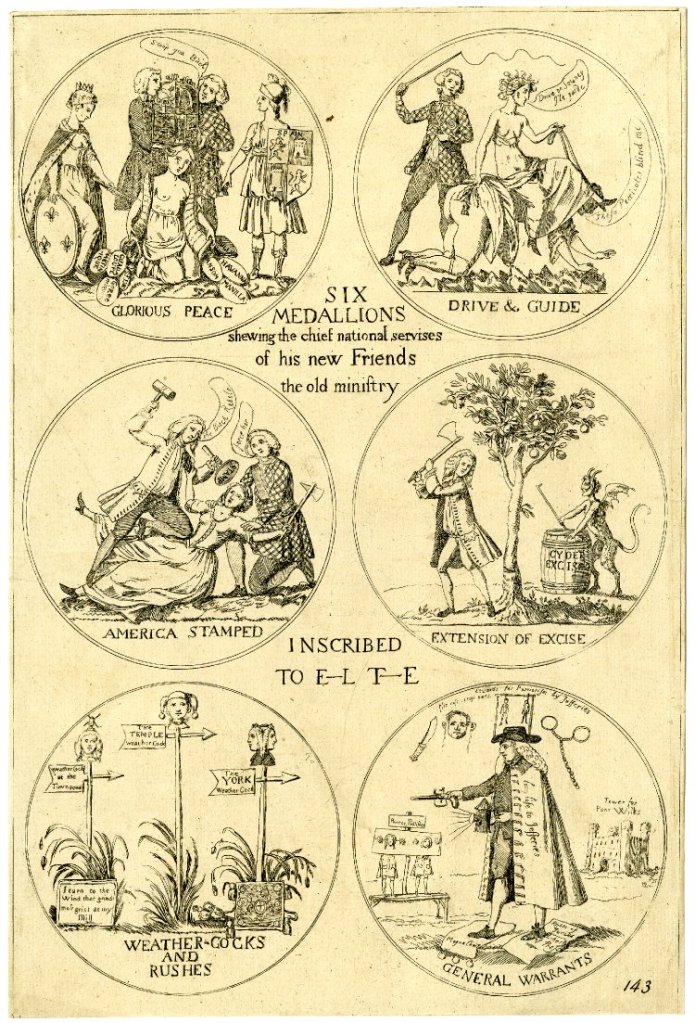

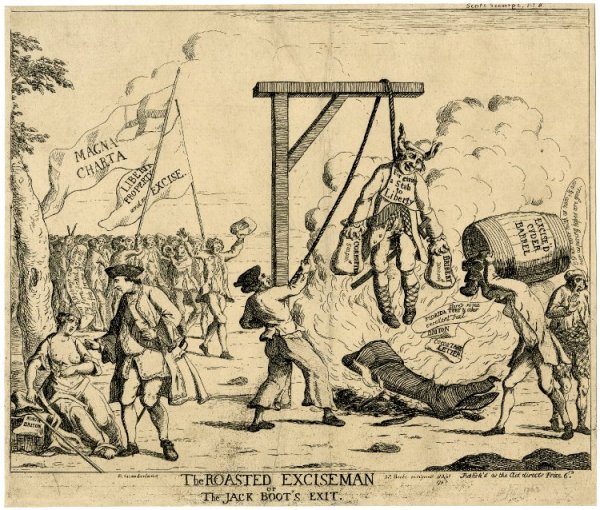

Below are some of my favourites, most of which I found by searching the word “disgrace”. To set them in their proper context I’ve thrown in some of the great petitioning campaigns from British history, just so we can see how far we’ve come. Petitions, for instance, were instrumental in the abolition of the slave trade in 1807. By 1792, the anti-slavery campaign had managed to gather 390,000 signatures in over 500 petitions calling for the abolition of the slave trade. Perhaps you remember the scene in Amazing Grace where William Wilberforce lays down a monster petition in parliament?

Below are some of my favourites, most of which I found by searching the word “disgrace”. To set them in their proper context I’ve thrown in some of the great petitioning campaigns from British history, just so we can see how far we’ve come. Petitions, for instance, were instrumental in the abolition of the slave trade in 1807. By 1792, the anti-slavery campaign had managed to gather 390,000 signatures in over 500 petitions calling for the abolition of the slave trade. Perhaps you remember the scene in Amazing Grace where William Wilberforce lays down a monster petition in parliament?

200 years after Parliament carried out the people’s wishes and put an end to the transatlantic slave trade, the British government disgracefully rejected a call to “Unban Jin from SmashUK“:

200 years after Parliament carried out the people’s wishes and put an end to the transatlantic slave trade, the British government disgracefully rejected a call to “Unban Jin from SmashUK“:

From what I can gather, SmashUK is the UK Smash Bros championship. We do not know who Jin is or what he/she did to get themselves banned, but David Cameron will apparently not be caving in to public pressure to resolve the situation. The SmashUK community have made much use of the petitions website, but their impassioned calls for the government to “Bring Rayman into Super Smash Bros. for Wii U and Nintendo 3DS” were also rejected:

From what I can gather, SmashUK is the UK Smash Bros championship. We do not know who Jin is or what he/she did to get themselves banned, but David Cameron will apparently not be caving in to public pressure to resolve the situation. The SmashUK community have made much use of the petitions website, but their impassioned calls for the government to “Bring Rayman into Super Smash Bros. for Wii U and Nintendo 3DS” were also rejected:

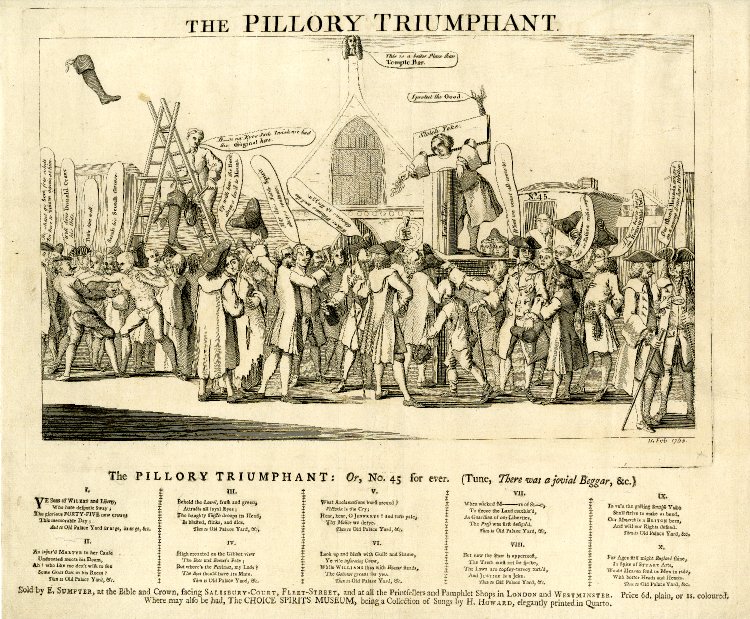

One of the greatest petitioning campaigns of the nineteenth century was organized by the Chartists, the working class political reform movement who called for votes for every man over 21, the secret ballot, and the abolition of property qualifications for MPs. In 1848, the Chartists assembled for a mass demonstration on Kennington Common and presented a petition to parliament which gathered at least 1.9million signatures:

One of the greatest petitioning campaigns of the nineteenth century was organized by the Chartists, the working class political reform movement who called for votes for every man over 21, the secret ballot, and the abolition of property qualifications for MPs. In 1848, the Chartists assembled for a mass demonstration on Kennington Common and presented a petition to parliament which gathered at least 1.9million signatures:

Increasing suffrage, large-scale political reform – quite an important and noble cause. But what’s more important in this day and age is remembering the true meaning of Christmas: Glenn Hoddle.

Sure, we have the right to vote, but do we have the right to enjoy little toys with our Frosties? LIKE HELL WE DO:

Sure, we have the right to vote, but do we have the right to enjoy little toys with our Frosties? LIKE HELL WE DO:

Searching “bring back” on the petitions website leads to a treasure trove of nostalgic fury. Mind you, you first have to get past the 300 or so petitions demanding that we bring back national service, corporal punishment and the death penalty:

Searching “bring back” on the petitions website leads to a treasure trove of nostalgic fury. Mind you, you first have to get past the 300 or so petitions demanding that we bring back national service, corporal punishment and the death penalty:

After these come a slaver of gluttons (google it) demanding that the government intervenes to bring back their favourite foods. First up it’s the McDonald’s big breakfast, disgracefully cancelled without warning:

Next, KFC Hotrods, because they’re in the national interest:

Next, KFC Hotrods, because they’re in the national interest:

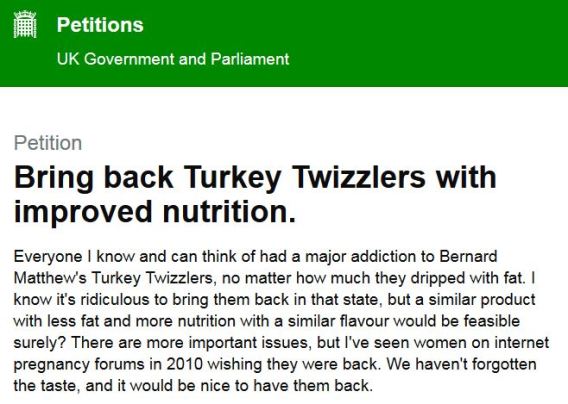

Third, the Jamie Oliver haters who just want their precious Turkey Twizzlers…

Third, the Jamie Oliver haters who just want their precious Turkey Twizzlers…

…or maybe Turkey Twizzlers with added nutrition:

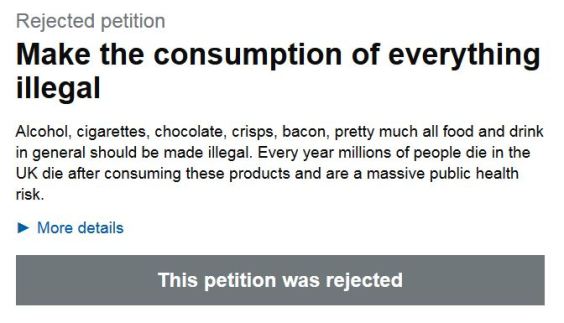

Perhaps the image of Turkey Twizzlers dripping with fat has disgusted you so much that wish the government could actually intervene to stop us eating such filth? Here, this petition should have you covered:

Perhaps the image of Turkey Twizzlers dripping with fat has disgusted you so much that wish the government could actually intervene to stop us eating such filth? Here, this petition should have you covered:

Wording a petition is always pretty tricky. If you are going to petition the government, I advise making it clear what you actually want:

Wording a petition is always pretty tricky. If you are going to petition the government, I advise making it clear what you actually want:

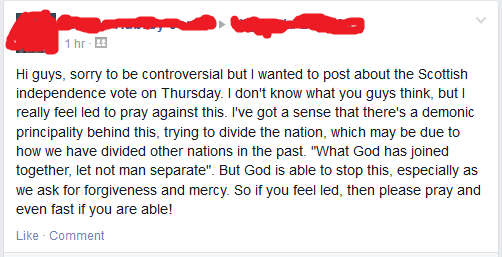

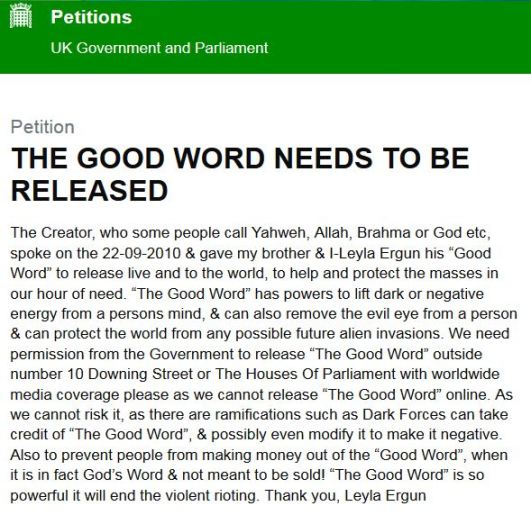

After a couple of hours scouring the petitions website, things began to get a little weird. There were the religious nutjobs…

After a couple of hours scouring the petitions website, things began to get a little weird. There were the religious nutjobs…

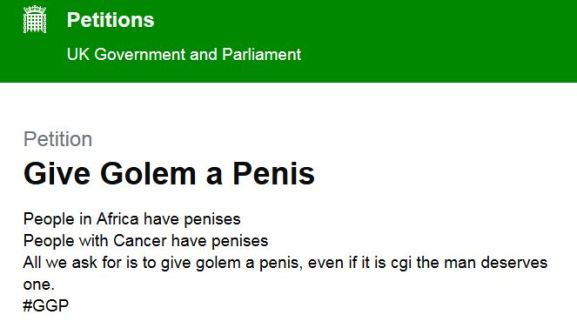

…followed by the sci-fi geeks…

…followed by the sci-fi geeks…

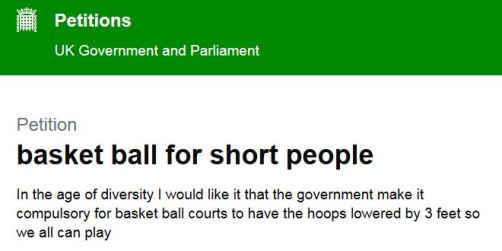

…and lastly the downright surreal:

…and lastly the downright surreal:

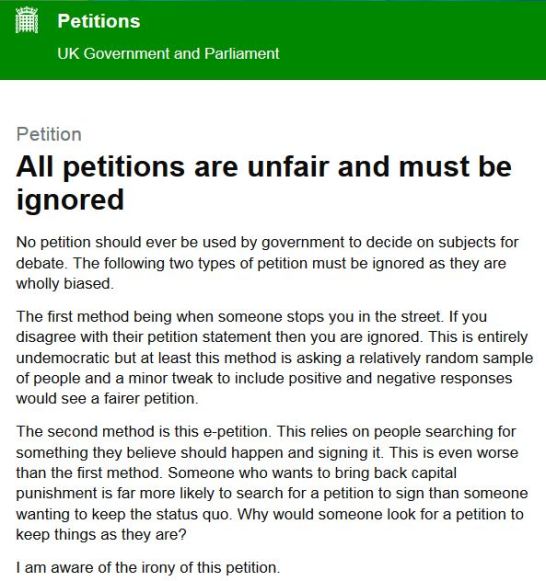

After all this, some of you may be thinking that the government petitions website it pretty damn useless. Maybe you even think it should be abolished? Well funnily enough…

After all this, some of you may be thinking that the government petitions website it pretty damn useless. Maybe you even think it should be abolished? Well funnily enough…

The government wanted to listen to this petition, but feared opening up some sort of cosmic rift in the ensuing paradox.

The government wanted to listen to this petition, but feared opening up some sort of cosmic rift in the ensuing paradox.

I could go on. I really could. There are so many, and they’re all so stupid. But why not visit the website and find your own favourites? But let’s take a moment to be thankful that we have both the right and the opportunity to be this stupid. We can bother the government with whatever little annoyance is preying on our mind, and the advent of the digital age has allowed the government to ignore our petitions in a whole new online world.

Let’s finish with this: